Historical review

From the beginnings of Slavic studies in Graz to the present day

On March 21, 1870, the classical philologist and Slavicist Gregor Krek is appointed Professor Extraordinarius for Slavic Philology. The establishment of the first chair of Slavic Studies at the University of Graz - Krek was appointed full professor of the subject in 1875 - was due to the efforts of Classical Philology, German Studies and Romance Studies (Italian Studies) to close a gap in research and teaching on comparative historical linguistics, It was also argued that "the population of the Styrian lowlands largely belongs to the Slavic tribe and, in addition, many students of Slavic origin from Carniola, Croatia, the coastal region and Dalmatia attend this university and should be given the opportunity to listen to lectures on Slavic grammar and literature" (Höflechner, Die Geisteswissenschaftliche Fakultät, 48).

While Krek's appointment marked the beginning of academic Slavic studies here, Slovenian had already been represented at the University of Graz before that, especially as courses in midwifery and medicine (Anton Buck, Matthias Goriupp, Johann Kömm) had also been held in Slovenian since the last quarter of the 18th century. At the instigation of the lawyer and founder of the scientific society Societas Slovenica Johann Nepomuk Primitz (Janez Nepomuk Primic), the establishment of a three-year professorship for Slovenian was approved at the then Jesuit University in 1811, which Primic himself held from February 19, 1812 until his illness in the autumn of 1813. In 1823, he was succeeded by the theologian and lawyer Coloman Quass (Koloman Kvas), who was employed at the university until 1867 as an "extraordinary teacher of the Windish language" and holder of the "chair for the Windish language". Theology (Matthias Robitsch, Josef Tosi) and law (Johann Kopatsch, Josef Krainz, Josef Michael Skedl) were also taught in Slovene for some time after 1848.

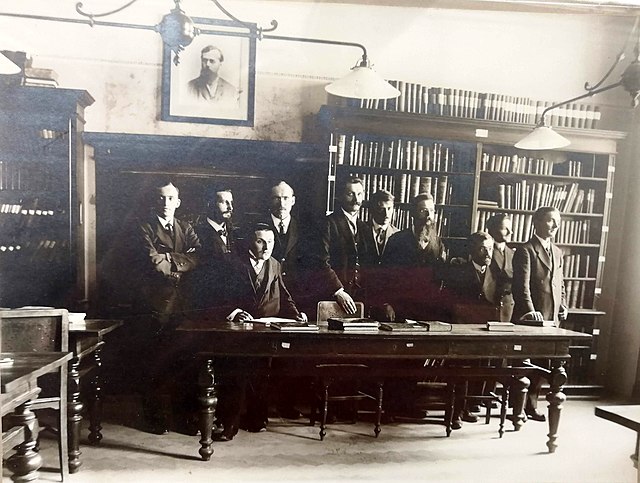

On April 2, 1892, the Imperial-Royal Ministry of Culture and Education approves the establishment of a seminar for Slavic philology. Funds were also provided for a "specialized library in the field of Slavic studies". The new institute was housed on the 2nd floor of the main building. It had two rooms and four desks with three workstations each. In the first three years, the number of seminar members was never less than ten (Krones, Geschichte der Karl-Franzens-Universität, 64-65).

As a result of political efforts in the Vienna Imperial Council to create an associate professorship in Slovene Studies in Graz, the Slavicist and Miklošič student Karel Štrekelj was appointed associate professor of "Slavic philology with special emphasis on the Slovene language and literature" in October 1896. This made Slavic studies the second new philological discipline to be given a second professorship. Originally, the professorship was intended for Vatroslav Oblak, a student of Jagić who had been teaching in Graz since 1894, but he died.

In 1902, after Krek's retirement, the Slavicist Matija Murko was appointed to the chair of Slavic philology. Karel Štrekelj, who was appointed full professor in 1908 due to an impending dismissal to Sofia, was followed in 1913 by the Indo-Europeanist and Slavicist Rajko Nahtigal. After Murko was appointed to the University of Leipzig, Nahtigal was made a full professor in 1917. In December 1918, shortly after his habilitation, the linguist Fran Ramovš left Graz, following an appointment to the commission for the founding of the University of Ljubljana. Nahtigal also moved to the newly founded university in 1919 and was involved in the development of Slavic studies there.

It was not until 1923 that the vacancy of both chairs, which had lasted several years, ended when the Leipzig Slavicist Heinrich Felix Schmid was appointed to the Chair of Slavic Philology; the second chair was vacated. Schmid works on comparative Slavic legal history and legal terminology, becoming a full professor in 1929. After the National Socialists came to power, he was arrested, retired and conscripted into the Wehrmacht.

From 1941, the Indo-Europeanist and Slavicist Bernd von Armin, who researched Old Bulgarian texts, South Slavic dialectology and astronomy, taught at Slavic Studies. He expected to be appointed to the University of Vienna, but was drafted into the Wehrmacht in 1944 and died soon after his return from captivity.

In 1943, Simon Pirchegger, a habilitated Slavicist and place name researcher, was assigned as an associate professor at the University of Graz, from where he had been expelled in 1934 due to his agitation for National Socialism. He was dismissed from his post in 1945.

Schmid returned to the University of Graz after the end of the war and accepted the professorship for Slavic linguistics and Eastern European history at the University of Vienna in 1948. His student Josef Matl, who wrote numerous works on comparative Slavic literary, cultural, social and intellectual history, particularly in South-Eastern Europe, and affirmed Graz as a center of Balkan studies in the 1960s, was appointed his successor. Under Matl's aegis, the Department of Slavic Philology is renamed the Institute of Slavic and Southeast European Studies. In 1969, the institute was given its current name.

With the appointment of the Slavicist Stanislaus Hafner, the "second" Slavicist chair was re-established in 1964. Hafner's research included Serbian medieval literature and the history of Austrian Slavic studies. He is appointed full professor in 1967 and in 1975, together with Erich Prunč (assistant at Slavic Studies from 1968), initiates the long-term project "Inventory of the Slovene vernacular in Carinthia", which is continued by Ludwig Karničar from 1989.

In 1968, Linda Sadnik was the first woman to be appointed to the Slavic Department in Graz. Matl's student and successor focuses on research into Old Church Slavonic and Old Bulgarian and is regarded as the founder of the "Graz School", from which Herbert Schelesniker (Innsbruck), Klaus Trost (Regensburg), Wolfgang Eismann (Oldenburg, Trier, Graz), Heinz Miklas (Vienna), Rudolf Aitzetmüller (Würzburg) and Harald Jaksche (Mannheim, Freiburg, Bern, Graz) emerge, among others.

In the 1970s, new positions were created for young academics. One of the positions was held by the Slavicist Eleonore Ertl from 1970; she was followed by the South Slavicists Manfred Trummer (1971) and Wolfgang Steininger (1972), the Russianist and Balkanologist August Maximilian Hendler (1976), the Russianist Heinrich Pfandl (1978) and the Russianist and Slovenianist Ludwig Karničar (1979).

Following the premature retirement of Linda Sadnik in 1975, Harald Jaksche was appointed to the Chair of Slavic Philology in 1978. Until his retirement in 1989, he worked primarily on contemporary Russian language and literature as well as Church Slavonic.

Wolfgang Eismann succeeded Stanislaus Hafner in 1988. He conducts research on Slavic cultural, literary and intellectual history, in particular Russia and the South Slavic countries, as well as on the theory of so-called small forms, Slavic phraseology and parömiology. In the same year, Erich Prunč, who habilitated in 1984, was appointed to the Chair of Translation Studies at today's Institute for Theoretical and Applied Translation Studies, with which the Institute of Slavic Studies has been associated in many areas since its foundation in 1946.

After being housed in the Meerscheinschlössl in the post-war period and later in Heinrichstraße 26 and partly in Mozartgasse 14, the Institute moved into its current premises in the "Wall Building" in 1994. During these years, the institute expands once again and extends its research and teaching profile with the semiotician and Slavicist Peter Grzybek (1992) and the Russianist and West Slavicist Peter Deutschmann (1995), who is appointed to the University of Salzburg in 2013. 1996 Branko Tošović is appointed to the Chair of Slavic Philology, which has been vacant since 1989. He conducts research into the contrastive linguistics and stylistics of Bosnian, Croatian and Serbian and establishes the GRALIS research portal.

Following the retirement of Wolfgang Eismamann, Renate Hansen-Kokoruš took over the vacant professorship for Slavic Studies (Literature and Cultural Studies) in 2009 and was appointed university professor in 2011. She researches modern Bosnian, Croatian, Serbian and Russian literature, film, intertextuality and questions of narratology. Following the departure of Renate Hansen-Kokoruš, Sonja Koroliov was appointed to the three-year professorship for Slavic Studies (Literary and Cultural Studies) in 2019.

Currently teaching at the Institute of Slavic Studies are Andreas Leben, who was appointed to the newly created Professorship of Slavic Studies (Slovenian Studies) in 2010, Boban Arsenijević, who succeeded Branko Tošović as Professor of Slavic Linguistics in 2016, and Tatjana Petzer, who took up the Professorship of Slavic Literary and Cultural Studies in 2023.

In the last years, numerous young academics have been employed at the Institute, including Svitlana Antonyuk, Agnieszka Będkowska-Kopczyk, Anastasia Chuprina, Mariya Donska, Urh Ferlež, Miriam Finkelstein, Lisa Haibl, Ingeborg Jandl, Emmerich Kelih, Felix Kohl, Goran Lazičić, Claudia Mayr-Veselinović, Stefan Milosavljević, Natalija Milovanović, Elena Popovska, Maria Katarzyna Prenner, Dària Seres, Dijana Simić, Marko Simonović, Arno Wonisch, Olesia Zalkowski, Yvonne Živković. The Senior Lecturers (currently Dagmar Gramshammer-Hohl), Lecturers (currently Ivana Bulić, Iryna Orlova, Michaela Winkler), lecturers abroad and teaching assistants also contribute to research and teaching (see current number of staff).

In2020, the Institute celebrated 150 years of Slavic Studies at the University of Graz, including with the international conference "Slawistik aktuell" (June 2-4).

Grzybek, Peter (2008): Slavistik in Graz / Slavistika v Gradcu. Signal 2007/2008, 183-207.

Hafner, Stanislaus (1972): Die Slawistik an der Universität in Graz bis 1918. Anzeiger für Slavische Philologie 6, 4-13.

Hafner, Stanislaus (1985): History of Austrian Slavic Studies. In: Hamm, Josef; Wytzrens, Günther (eds.): Contributions to the history of Slavic studies in non-Slavic countries. Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 11-88.

Höflechner, Walter (2005): Die Geisteswissenschaftliche Fakultät der Universität Graz zur Zeit von Gregor Krek. Anzeiger für Slavische Philologie 33, 43-51.

Höflechner, Walter (2006): History of the Karl-Franzens-University of Graz. From the beginnings to the year 2005. Graz: Grazer Universitätsverlag, Leykam.

Kernbauer, Alois (2005): Gregor Krek and the beginnings of Slavic Studies at the University of Graz: Anzeiger für Slavische Philologie 3, 53-70.

Krones, Franz von (1886): Geschichte der Karl-Franzens-Universität in Graz. Festgabe zur Feier ihres dreihundertjährigen Bestandes. Graz: Publishing house of the Karl-Franzens-University.

Reichmayr, Michael (2003): Ardigata! Krucinal! A Slovenian swear dictionary, based on the work of Josef Matl (1897-1974) on German-Slavic linguistic and cultural contact. With a foreword by Paul Parin. Graz: Article VII Cultural Association for Styria.

Sadnik, Linda (1972): Slavic Studies at the University of Graz after 1918. Anzeiger für Slavische Philologie 6, 14-19.

Šumrada, Janez (2002): Janez Primic and the foundation of the first Slovenianist chair in Graz in 1811. Anzeiger für Slavische Phil ologie 30, 7-20.